Music

The music in the processional is monophonic chant, which means it has a single, vocal melody and no accompaniment or harmony. Chant music written for the western church is often called plainchant or Gregorian chant, and it was the dominant form of religious music throughout most of the Middle Ages.

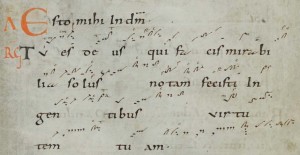

Early neumes written above a chant. Codex Sangallensis 359, 922-926, Abbey Library of Saint-Gall, Switzerland

Plainchant has always joined words and tones very closely together, but musical literacy is a much newer phenomenon than verbal literacy. For centuries, chant music was passed through the generations by memorization and repetition. To Isidore of Seville, writing in the seventh century, music was a deeply transient experience, as he wrote, “Indeed, unless sounds are kept in the memory of a person, they pass away, for sounds can not be written.”[1] The earliest western Christian system for writing music probably developed no earlier than the eighth century. It used symbols called neumes to mark patterns of rising and falling tones above lines of written words.[2]

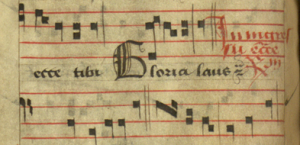

The upper lines begins with a C clef, the lower line, an F clef. The middle of the clef signs mark C and F, respectively. Poissy Processional, Bryn Mawr College, f. 19v

In the eleventh century, an Italian monk called Guido d’Arezzo set the neumes on a four line staff so that their tonal values could be read and interpreted consistently even by musicians with relatively little training.[3] This medieval staff, which our manuscript uses, is closely related to the modern staff, although it is not written in treble, bass, alto, or tenor clefs, but in C and F clefs, in which a movable clef sign indicates the location of middle C or of the F a fifth below middle C on the staff.

The neumes can be written singly or in connected groups. In general, each syllable of chant is accompanied either by a single neume (syllabic chant) or by a connected neume group (neumatic chant). More rarely, a syllable may take several neumes or neume groups (melismatic chant). The rhythms of chants do not seem to be notated, and there is controversy about how they would have been performed in the Middle Ages.[4]

Medieval chants were organized into eight modes, identified by the chant’s final note and by its overall tonal range. The church modes were imagined to correlate with ancient Greek modes, from which they are actually quite different.[5] They present a greater musical diversity than the modern major-minor system, and operate according to different principles, largely because they are not built in the same way around the idea of a tonal center.[6] Chant melodies usually move in whole steps up and down the tones of a mode. Jumps of a third are relatively common, but larger jumps are more rare.[7]

There are several common genres of chant, which are different in their musical structure and their performance. Most of the chants in the Poissy processional are responsories and antiphons, which are often performed as a sort of musical conversation between a soloist or a small group and a choir. Both forms alternate between verses and refrains, although they are differently structured and have different tonal characteristics. Although most antiphons are sung in response to the yearly cycle of psalms and canticles, there is also a class of processional antiphons, like the ones that appear in our book, which are longer, independent chants that can often be musically elaborate.[8] The four chants recorded on this site are all antiphons, although they are differently structured. In the first chant of the Candlemas procession, for instance, which begins, “Lumen ad revelationem…,” the choir sings the first refrain, which runs through the first two lines of notation, and then it alternates with the soloists, who take up the different verses. However, the choir sings second chant, beginning “Ave gratia plena…,” through entirely with no responses or repeats.

The manuscript’s music is part of a very old tradition that continues in the present, because it has been preserved in practice and in books. Many of the chants in the manuscript are written in nearly identical musical form in very long book of commonly used chants, Liber Usualis, which was created and edited over the last century and a half by the Benedictine monks of the Solesmes monastery in France.[9] In addition to words, notes, and instructions, the Liber also marks the mode and genre of each chant.

[1] “Nisi enim ab homine memoria teneantur soni, pereunt, quia scribi non possunt.” Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, 3:16. As mentioned in Kelly, Capturing Music, 16.

[2] For a description of chant notation see Richard H. Hoppin, Medieval Music (New York: W.W. Norton, 1978), 55-60.

[3] In addition to devising the staff, Guido d’Arezzo also invented a system called solmization, in which each note was associated with one of the syllables, ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, that begin the phrases of a certain hymn to St John the Baptist, which reads, “Ut quaeant laxis, Resonare fibris/ Mira gestorum Famuli tuorum/ Solve pollute Labii reatum/ Sancte Iohannes.” Solmization became an indispensable teaching tool (as everyone who has watched The Sound of Music knows), but it also helped its maker to develop the tonal theory of western chant around interlocking sets of hexachords, which are groups of six notes with intervals of two whole-tones, a semi-tone, and two more whole-tones. See, Giulio Cattin, Music of the Middle Ages, vol. I, Trans. Steven Botterill (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 56-60 and Hoppin, Medieval Music, 63-4.

[4] Hoppin, Medieval Music, 88-90.

[5] Hoppin, Medieval Music, 69.

[6] Leonard Bernstein gave a Young People’s Concert on 23 November, 1966, in which he discussed the difference between a scale and a mode. His description may be useful to newcomers to musical theory. The full talk is available on youtube. (He gets his orchestra to sing a line of chant. It’s fabulous!)

[7] Hoppin, Medieval Music, 75

[8] On processional antiphons, see David Hiley, Western Plainchant: A Handbook, (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993), 100-104. On the structures of antiphons and responsories, see also, Andrew Hughes, Medieval Manuscripts for Mass and Office: A Guide to Their Organization and Terminology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), 26-34.

[9] Several editions of the Liber Usualis, including the 1957 and 1961 volumes, are available for use and download online.